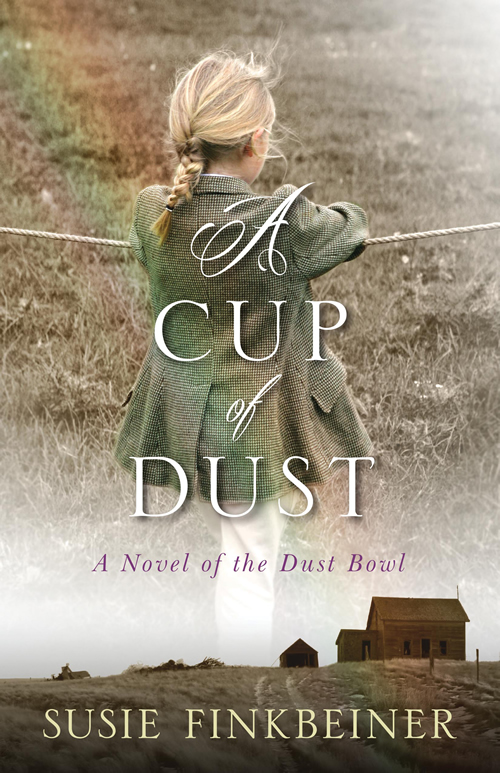

I received an e-mail from Susie Finkbeiner one morning alerting a post she wrote, "

," and this photo found in an antique store that revealed a love beyond measure.

"When I look into the eyes of the woman in the picture I found at the

antique store, that's what I see. Grace and determination and fierce

love.

"I don't know the real name of that woman. I never will, I guess. But to

me, she'll always be Mary Spence. She'll always be Pearl's own mama."

Survivors. Doing what they know to do.

Seasonal workers. Going half way across the country to find work picking vegetables, to care for family back home. Migrant worker camps ~ missing those left behind.

Only excitement lately is the train pulling in near us. Until the day one man getting off a boxcar with others, walks right to me and says, "Pearl?" Then he saunters off. How does he know my name? I am silent. I say nothing.

I am handed a birthday card every year that I am to hide from Mama ~ not signed, who is it from? There is more going on than the wind blowing the Oklahoma dust over the land. My Daddy's the sheriff. He and I are close. He is a good man and looks out for us.

A somber story of a harrowing time in history during the Great Depression. The loss wasn't as much about money as it was holding on to hope and dreams. There was not much money could buy. Shriveled up living left behind empty storefronts and a loss of neighbors, as those believing they traveled away to a better time. The better time actually was families ~ clinging to each other and helping out where they could. Sharing what they had, including kind and encouraging words for a better tomorrow as the storms abated and lives returned to an earlier time of green grass and fattened cattle.

Others may have had another view of the time, but this is Pearl's story. Fear held in, afraid if it dispelled all she knew to be true, it would collapse against the faint haze of the sun against the glowing dust piles as far as the eye could see.

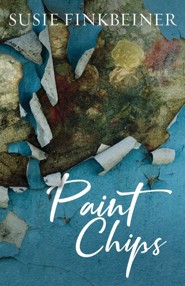

Wife. Mother. Novelist. Living the story.

Susie Finkbeiner is a stay-at-home mom, speaker, and author from West Michigan. Her previous books include

(2014). She has served as fiction editor and regular contributor to the Burnside Writers Guild and

magazine. Finkbeiner is an avid

,

is on the planning committee of the Breathe Christian Writers

Conference, and has presented or led groups of other writers at several

conferences.

I needed to give the Dust Bowl folks their chance to say, "See what

happened here? See how we survived. What we lost. What we gained. See

what you can learn from us about love and loyalty, faith and grit, loss

and hardship?"

***Thank you to Kregel Publications for inviting me to be part of the blog tour for

by Susie Finkbeiner. This review was written in my own words. No other compensation was received.***

CHAPTER PAST

Red River, Oklahoma

September 1934

As soon as I was off the porch and out of Mama’s sight, I pushed the

scuffed-up, hole-in-the-soles Mary Janes off my feet. They hurt like

the dickens, bending and cramping my toes and rubbing blisters on my

heels. Half the dirt in Oklahoma sifted in when I wore those shoes, tickling

my skin through thin socks before shaking back out. When I was

nine they had fit just fine, those shoes. But once I turned ten they’d gotten

tight all the sudden. I hadn’t told Mama, though. She would have dipped

into the pennies and nickels she kept in an old canning jar on the bottom

of her china cabinet. She would have counted just enough to buy a new

pair of shoes from Mr. Smalley’s grocery store.

I didn’t want her taking from that money. That was for a rainy day, and

we hadn’t had anything even close to a rainy day in about forever.

Red River was on the wrong side of No Man’s Land in the Panhandle.

The skinny part of Oklahoma, I liked to say. If I spit in just the right direction,

I could hit New Mexico. If I turned just a little, I’d get Colorado.

And if I spit to the south, I’d hit Texas. But ladies didn’t spit. Not ever.

That’s what Mama always said.

I leaned my hip against the lattice on the bottom of our porch. Rolling

off my socks, I kept one eye on the front door just in case Mama stepped

out. She was never one for whupping like some mothers were, but she had

a look that could turn my blood cold. And that look usually had a come-to-Jesus meeting that followed close behind it.

She didn’t come out of the house, though, so I shoved the socks into my

shoes and pushed them under the porch.

Bare feet slapping against hard-as-rock ground felt like freedom.

Careless, rebellious freedom. The way I imagined an Indian girl would

feel racing around tepees in the days before Red River got piled up with

houses and ranches and wheat. The way things were before people with

white faces and bright eyes moved on the land.

I was about as white faced and bright eyed as it got. My hair was the

kind of blond that looked more white than yellow. Still, I pretended my

pale braids were ink black and that my skin was dark as a berry, darkened

by the sun.

Pretending to be an Indian princess, I ran, feeling the open country’s

welcome.

If Mama had been watching, she would have told me to slow down and

put my shoes back on. She surely would have gasped and shook her head

if she knew I was playing Indian. Sheriff’s daughters were to be ladylike,

not running wild as a savage.

Mama didn’t understand make-believe, I reckoned. As far as I knew

she thought imagination was only for girls smaller than me. “I would’ve

thought you’d be grown out of it by now,” she’d say.

I hadn’t grown out of my daydreams, and I didn’t reckon I would. So I

just kept right on galloping, pretending I rode bareback on a painted pony

like the one I’d seen in one of Daddy’s books.

Meemaw asked me many-a-time why I didn’t play like I was some girl

from the Bible like Esther or Ruth. If they’d had a bundle of arrows and

a strong bow I would have been more inclined to put on Mama’s old robe

and play Bible times.

I slowed my trot a bit when I got to the main street. A couple ladies

stood on the sidewalk, talking about something or another and waving

their hands around. I thought they looked like a couple birds, chirping at

each other. The two of them noticed me and smiled, nodding their heads.

“How do, Pearl?” one of them asked.

“Hello, ma’am,” I answered and moved right along.

Across the street, I spied Millard Young sitting on the courthouse

steps, his pipe hanging out of his mouth. He’d been the mayor of Red

River since before Daddy was born. I didn’t know his age, exactly, but he

must have been real old, as many wrinkles as he had all over his face and

the white hair on his head. He waved me over and smiled, that pipe still

between his lips. I galloped to him, knowing that if I said hello he’d give

me a candy.

Even Indian princesses could enjoy a little something sweet every now

and again.

With times as hard as they were for folks, Millard always made sure he

had something to give the kids in town. Mama had told me he didn’t have

any grandchildren of his own, which I thought was sad. He would have

made a real good grandpa. I would have asked him to be mine but didn’t

know if that would make him feel put upon. Mama was always getting

after me for putting upon folks.

“Out for a trot?” he asked as soon as I got closer to the bottom of the

stairs.

“Yes, sir.” I climbed up a couple of the steps to get the candy he offered.

It was one of those small pink ones that tasted a little like mint-flavored

medicine. I popped it in my mouth and let it sit there, melting little by

little. “Thank you.”

He winked and took the pipe back out of his lips. It wasn’t lit. I wondered

why he had it if he wasn’t puffing tobacco in and out of it.

“Looking for your sister?” His lips hardly moved when he talked. It

made me wonder what his teeth looked like. I’d known him my whole life

and couldn’t think of one time that I’d seen his teeth. “Seen her about half

hour ago, headed that-a-way.” He nodded out toward the sharecroppers’

cabins.

“Thank you,” I said with a smile.

“Hope you catch her soon,” he said, wrinkling his forehead even more.

“Her wandering off like that makes me real nervous.”

“I’ll find her. I always do,” I called over my shoulder, picking up my

gallop. “Thanks for the candy.”

“That’s all right.” He nodded at me. “Watch where you’re going.”

I turned and headed toward the cabins, hoping to find my sister there

but figuring she’d wandered farther out than that.

My sister was born Violet Jean Spence, but nobody called her that. We

all just called her Beanie and nobody could remember why exactly. Daddy

had told me that Beanie was born blue and not able to catch a breath.

He’d said he had never prayed so hard for a baby to start crying. Finally,

when she did cry and catch a breath, she turned from blue to bright pink.

Violet Jean. The baby born blue as her name. Just thinking on it gave me

the heebie-jeebies.

When I needed to find Beanie, I knew to check the old ranch not too

far outside town. My sister loved going out there, being under the wide-open

sky. I was sure that if a duster hit, God would know to look for her

at that ranch, too.

Meemaw had told me that God could see us no matter

where we went, even through all the dust. I really hoped that was true for

Beanie’s sake.

Meemaw had told me more than once that God saved us from the dust.

So I figured He was sure to see me even if Pastor said the dust was God

being mad at us all.

In the flat pasture, cattle lowed, pushing their noses into the dust,

searching out the green they weren’t like to find. I expected I’d find Beanie

standing at the fence-line, hands behind her back so as to remember not

to touch the wire. Usually she’d be there looking off over the field, eyes

glazed over, not putting her focus on anything in particular.

Daddy said she acted so odd because of the way she was born. She

could see and hear everything around her. But when it came to understanding,

that was a different thing altogether.

I found Beanie at the ranch, all right. But instead of looking out at

the pasture, she was sitting in the dirt, her dress pulled all the way up to

her waist, showing off her underthings in a way Mama would never have

approved of. Mama would have rushed over and told Beanie to put her

knees together, keep her skirt down, and sit like a lady. I didn’t think my

sister knew what any of that meant.

Being a lady was just one item on the laundry list of things my sister

couldn’t figure out. I wondered how much that grieved Mama.

Mama had told me Beanie was slow. Daddy called her simple. Folks

around town said she was an idiot. I’d gotten in more than one fight over a

kid calling my sister a name like that. Meemaw had said those folks didn’t

understand and that people sometimes got mean over what they didn’t

understand.

“It ain’t no use fighting them,” she had told me. “One of these days

they’ll figure out that we’ve got a miracle walking around among us.”

Our own miracle, sitting on the ground grunting and groaning and

playing in dirt.

“Beanie.” I bent at the waist once I got up next to her. My braids swung

over my shoulders. “We gotta go home.”

The tip of Beanie’s nose stayed pointed at the space between her

spread out legs. Somehow she’d gotten herself a tin cup. Its white-and-blue

enamel was chipped all the way around, and I figured it was old.

She found things like that in the empty houses around town. Goodness

knew there were plenty of abandoned places for her to explore around Red

River. Half the houses in Oklahoma stood empty. Everybody had took up

and moved west, leaving busted-up treasures for Beanie to find.

She’d hide them from Mama under our bed or in our closet. Old, tattered

scraps of cloth, a busted up hat, a bent spoon. Everything she found

was a treasure to her. To the rest of us, it was nothing but more junk she’d

hide away.

“You hear me?” I asked, tapping her shoulder. “We gotta go.”

She kept on digging in the dirt with that old cup like it was a shovel.

Once she got it to overflowing, she held it in front of her face and tipped

it, pouring it out. The grains of sand caught in the air, blowing into her

face. I stood upright, pulling the collar of my dress over my face to block

out the dust. She just didn’t care—she let it get in her mouth and nose

and eyes.

“That’s not good for you,” I said. “Don’t do that anymore.”

Little noises came out her mouth from deep inside her. Nothing anybody would have understood, though. Mostly it was nothing more

than short grunts and groans. Meemaw liked to think the angels in

heaven spoke that same, hard tongue just for Beanie. Far as I knew it was

nothing but nonsense. Beanie was sixteen years old and making noises

like a two-year-old. She could talk as well as anybody else, she just didn’t

want to most of the time.

“Get up. Mama’s waiting on us.” I grabbed hold of her arm and pulled.

“Put that old cup down, and let’s go.”

Scooping a cup of dust, she finally looked at me. Not in my eyes,

though, she wouldn’t have done that. Instead, she looked at my chin and

smiled before dumping the whole cupful on my foot.

Some days I just hated my sister so hard.

“I seen a horny toad,” Beanie said, pushing against the ground to stand

herself up. She stopped and leaned over, her behind in the air, to refill the

cup. “It had blood coming out its eyes, that horny toad did.”

“So what.” I took her hand. Scratchy palmed, she left her hand limp in

mine, not making the effort to hold me back. “Mama’s gonna be sore if

we don’t get home.”

“Must’ve been scared of me. That toad squirted blood outta its eye right

at me. Didn’t get none on me though.” She looked down at her dress to

make sure as she shuffled her feet, kicking up dust. Her shoes were still

on, tied up tight on her feet so she wouldn’t lose them.

Mama moaned many-a-day about how neither of her girls liked to keep

shoes on.

“That toad wasn’t scared of you,” I said. “Those critters just do that.”

We took a few steps, only making it a couple yards before Beanie

stopped.

“Duster’s coming.” Dark-as-night hair frizzed out of control on her

head, falling to her shoulders as she looked straight up. Her big old beak

of a nose pointed at the sky. “You feel it?”

“Nah. I don’t feel anything.”

Her long tongue pushed between thin lips making her look like a lizard.

Her stink stung my nose when she raised both of her arms straight

up over her head. She would have stayed like that the rest of the day if I

hadn’t pulled her hand back down and tugged her to follow behind me.

After a minute or two she stopped again. “You feel that poke?” she

asked.

“Just come on.” Hard as I yanked on her arm, I couldn’t get her to budge.

Goose pimples bumped up on her arms. Then I felt them rise on mine.

A buzzing, fuzzing, sharp feeling on my skin caught the breath in my

lungs.

The same feeling we always got before a dust storm rolled through.

“We gotta get home.” Finally, my pulling got her to move, to run, even.

Flapping of wings and twittering of voice, a flock of birds flew over

us, going the opposite way. They always knew when a roller was coming,

all the birds and critters did. Beanie did, too. I wondered if she was part

animal for the way she knew things like that.

We stopped and watched the birds. Beanie’s coal black eyes and my

clear blue, watching the frantic flying. Beanie squeezed my hand, like we

really were sisters and not just one girl watching over the other. For a quick

minute, I felt kin to her.

Most of the time I just felt the yoke of her pushing me low, weighing

about as much as all the dust in Oklahoma.

~*~

The winds whipped around us, and a mountain of black dirt rolled

along, chasing behind us. Making our way in a straight path was near

impossible, so we followed the lines of wire fence, watching the electric

air pop blue sparks above the barbs. We got home and up the porch steps

just in time. Mama was watching for us, waving for us to get up the steps.

Reaching out, she pulled me in by the hand, our skin catching static, jolting

all the way through me and into Beanie.

Just as soon as we were inside, Mama closed and bolted the door. “It’s

a big one,” she said, shoving a towel into the space between the door and

the floor.

“Praise the Lord you girls didn’t get yourselves lost,” Meemaw said,

stepping up close and examining our faces. “You got any blisters? Last

week I seen one of the sharecropper kids with blisters all over his body

from the dust, even where his clothes covered his skin. And we didn’t have

nothing to soothe them, did we, Mary?”

“We did not.” Mama moved around the room, busying herself preparing

for the storm.

The nearest doctor was in Boise City, a good two-hour drive from Red

River, three if the dust was thick. When folks couldn’t get to the city or

didn’t have money to pay, they’d come to Meemaw and Mama. I thought

it was mostly because they had a cabinet full of medicines in our house.

Meemaw’d said, though, that it was on account of Mama had taken a year

of nurses’ training before she met Daddy.

“That poor boy. We had to clean out them sores with lye soap. I do

believe it stung him something awful.” Meemaw shook her head. “Mary,

did we put in a order for some of that cream?”

“I did.” Mama plunged a sheet into the sink and pulled it out, letting

it drip on the floor. “Pearl, would you please help me? This is the last one

to hang.”

We hung the sheet over the big window in the living room. Mama’s

shoes clomped as she moved back from the window. My naked feet patted.

I remembered my shoes, still under the porch. I crisscrossed my feet, one

on top of the other, hoping she wouldn’t notice.

“You can dig them out in the morning,” Mama said, lifting an eyebrow

at me.

Mama never did miss a blessed thing.

Rumbling wind pelted the house with specks of dirt and small stones.

Mama pulled me close into her soft body.

“Don’t be scared,” she said, her voice gentle. “It’ll be over soon.”

Then the dust darkened the whole world.

Wind roared, shaking the windows and rattling doors. It pushed

against the house from all sides like it wanted to blow us into the next

county. I believed one day it would.

The dust got in no matter how hard we tried to keep it out. It worked

its way into a crack here or a loose floorboard there. A hole in the roof or a

gap in a windowsill. It always found a way in. Always won.

Dust and dark married, creating a pillow to smother hard on our faces.

Pastor had always said that God sent the dust to fall on the righteous

and unrighteous alike because of His great goodness. I didn’t know if

there were any righteous folk anymore. Seemed everybody had given over

to surviving the best they knew how. They had put all the holy church talk

outside with the dust.

Still, I couldn’t help but imagine that the dust was one big old whupping

from the very hand of God.

I wondered how good we’d all have to be to get God to stop being so

angry at us.

Pastor’d also said it was a bad thing to question God. If it was a sin, sure

as lying or stealing busted-up cups or tarnished spoons, I didn’t want any

part of it. I didn’t want to be the reason the dust storms kept on coming.

I decided to fold myself into my imagination instead of falling into sin.

I pretended the wind was nothing more than the breath of the Big Bad

Wolf, come to blow our brick house down. Problem was, no amount of

hairs on our chiny chin chins could refuse to let it in. Prayers and hollering

didn’t do a whole lot either, as far as I could tell.

The daydream didn’t work to push off my fear. Mama’s arm around me

tightened, and I turned my face toward her, pushing into the warmth of

her body. She smelled like talcum powder and lye soap.

I stayed just like that, pressed safely against her, until the rolling

drumbeat of the dust wall slowed and stopped and the witches’ scream of

wind quieted. The Lord had sent the dust, but He’d also sent my mama.

I wondered what Pastor would have to say about that. I wasn’t like to ask

though. That man scared me more than a rattlesnake. And he was just as

full of poison.

Mama loosened her arms and rubbed my back. “It’s done now,” she

said. “We made it.”

“Praise the Lord God Almighty,” Meemaw sang out.

Sitting up, I felt the grit the storm left behind on my skin and in my

hair and under my eyelids.

“You think Daddy’s okay?” I asked, blinking against the haze hanging

in the air.

“I have faith he is.” Mama stood and shook the dirt from her skirt. “I

would bet he’s worrying about us as much as we’re worrying about him.”

A flickering flame rose as Meemaw lit a lantern. It barely cut through

the thick air. Still, the light eased my fear.

Susie Finkbeiner A Cup of Dust, Kregel Publications, © 2015

For the first time, Amy Clipston’s beloved novella, Naomi’s Gift, is

paired with two never-before-seen stories from Kelly Irvin and Ruth Reid

in a beautiful, keepsake collection. These stories follow the moments

of unexpected love and joy three women experience during the holiday

season. Each novella focuses on the importance of family, faith and

hope not just during the holidays but all year-round.

For the first time, Amy Clipston’s beloved novella, Naomi’s Gift, is

paired with two never-before-seen stories from Kelly Irvin and Ruth Reid

in a beautiful, keepsake collection. These stories follow the moments

of unexpected love and joy three women experience during the holiday

season. Each novella focuses on the importance of family, faith and

hope not just during the holidays but all year-round.

Returning on the steamer back to Savannah for the trial, would her sanctuary at Indigo Point following the inquest be enough to quench her fears ~ of the unknown beyond her innocence?

Returning on the steamer back to Savannah for the trial, would her sanctuary at Indigo Point following the inquest be enough to quench her fears ~ of the unknown beyond her innocence?