Eli Brenneman leaves his Amish community in Sunrise, Delaware, upon receiving his draft notice during World War II. He serves as a

conscientious objector to war, being assigned to a Civilian Public

Service labor camp far from home.

Eli Brenneman leaves his Amish community in Sunrise, Delaware, upon receiving his draft notice during World War II. He serves as a

conscientious objector to war, being assigned to a Civilian Public

Service labor camp far from home.

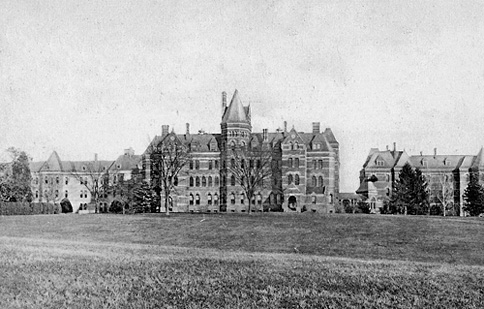

With overcrowding and need for additional staff, Eli is transferred with a unit to Hudson River State Hospital near Poughkeepsie, New York, as an attendant for the mentally unstable. There he meets nurse Christine Freeman, a young woman dedicated to her job as she strives to financially care for her family following the death of her two brothers overseas. She is uncertain how she is going to respond to Eli, although they must work together. A time of war, a time of grief.

Eli serves for eighteen months and comes home changed. With changes in her own personal life, Christine is in need of time to think through her future decisions. Eli offers her a time of rest at his family's farm. Bringing an English girl home with him isn't that much of a surprise to all in his community. He is remembered as looking out for himself and not the young women he meets at the Singings, bringing first one and then another home in his buggy.

Christine stays in a cottage with Eli's elderly aunt across the field from his family's farm home. Aunt Annie is one of my favorite characters in the story. She is a midwife and Christine's nursing fits right in. Eli's sister-in-law befriends Christine and stood out to me as a strong supporter.

I have not read the first story in the series, Promise to Return, but felt this second story was complete as a stand-alone novel. This story could be written today, as well as of the mid-1940s. Hmm... I was cautioning Christine, a lot like my husband does football replays! So well-written as the characters explore their options. Forgiveness with life insights given for each character view. For some it was too late; for others new beginnings. Very visual writings like walking alongside. Very good and complete!

| |

| Photograph Credit: Esther M. Byler |

***Thank you to author Elizabeth Byler Younts for the invitation to read and review your newest novel, Promise to Cherish, and to Howard Books. This review was written in my own words. No other compensation was received.***

Enjoy this excerpt from Promise to Cherish by Elizabeth Byler Younts ~ Chapter 1

CHAPTER 1

1945

January sunlight spilled onto Christine Freeman’s face and reflected off her glasses. She closed her eyes in the white light and pretended she wasn’t just standing in front of a window in the drab hospital hall. She had always loved mornings. And she would continue to find beauty in her mornings even while she worked at the dreary Hudson River State Hospital as a nurse for the mad. With almost no budget, the hospital was nothing more than a primitive asylum. Had it ever truly been an asylum for its patients? A sanctuary? A protection? A refuge?

She opened her eyes. Across the wintry lawn at the top of the hill stood the gothic Victorian Kirkbride structure. It was the hospital’s main structure and stood like a palace against the washed-out sky. Its green hoods pointed to the heavens. Its wards stretched in opposite directions like wings of an eagle, one for men and one for women. It was also where she lived, in one of the small apartments on the top floor. Though the Kirkbride building was designed to be a comfortable setting for the patients, giving them jobs and a purpose, during these bleak years of war many of those ideals were lost. The palatial building was more prisonlike than ever.

Edgewood, the two-story building Christine worked in, was dwarfish and rough by comparison. Being from nearby Poughkeepsie, she’d often viewed the hospital from the outside. How many times had she and her friends ridden their bikes out to the edge of town where the timeworn Victorian buildings stood, hoping to catch a glimpse of the lunatics. She had never imagined that she would work there someday.

Christine wanted to run down the path and away from this place. But there was no point entertaining such notions. Her family needed her to work. End of discussion. Their very survival depended on it.

A mournful cry from the nearby dorm room infiltrated her thoughts. She released a long exhale, then moved away from the window. She pulled at the tarnished gold chain from under her Peter Pan collar. The small cream-faced watch at the end of the necklace ticked almost soundlessly in her hand. Her twelve-hour day couldn’t wait any longer. After tucking the watch back beneath her pale blue and white uniform, she stepped inside the thirty-bed dorm that then slept over forty-five men. She scanned the room to find the moaning patient. The paint-chipped iron beds were crammed so tightly it was difficult to see. The few who refused to leave their beds or had been sedated during the night shift were the only rounded figures atop the cots.

Christine walked to the second row and went sideways through the narrow aisle to check on the noisy patient. Wally. Electroconvulsive therapy usually caused gastrointestinal and abdominal discomfort, but Wally’s always lasted longer than a typical patient’s. Christine didn’t have any medications with her but knew Dr. Franklin had a standing order of hyoscine to treat Wally’s nausea. Confirming his temperature was normal, she left the room.

She passed several of the rooms with two beds and a few with only one, usually retained for contagious patients. She would have to visit each as soon as she spoke with the night nurse to assess how her shift had gone.

Christine passed another dorm room with nearly fifty beds and let out a sigh, noticing how few of the beds had sheets. Even the mattresses themselves were thin and flimsy, covered in shabby vinyl and incapable of adding any warmth to their inhabitants. Though she’d gone through three years of nursing school at this very hospital, she had a difficult time growing accustomed to how little bedding and clothing the patients received. It was not as tragic in the summer—save for the patients’ modesty—but when the autumn breezes brought in winter storms, a sense of failure came over her.

The Kirkbride patients were supposed to make clothing for everyone, but with dwindling supplies and money everything was at a minimum or a standstill. The state only provided one sheet and one set of clothing per patient. If they were soiled, the patient would have to go without. Her efforts to coordinate a clothing drive had been thwarted. The town wanted little to do with the institution. Outside of some extraordinary donation, the funding they needed would have to come from the state alone.

As she moved on, Christine dreaded the scent of urine that lived in the very concrete blocks of the building’s walls. The smell in the day room heightened. The odor in the hallway was mild by comparison.

“Remember, Christine,” she said quietly to herself as she pulled open the door. “This is the day the Lord has made. I will rejoice and be glad.”

Rejoice. Be glad. Rejoice. Be glad.

In order to accept the difficulties, she focused on the good she wanted to do for her patients and her family. With her brothers dead and buried half a world away in a war-torn country, her parents needed her income. That thought alone gave her the encouragement she needed to continue.

Christine’s lips stretched into a forced smile, she pushed her glasses up on the bridge of her nose, and walked into the day room. Every corner of the large, square, gray room was filled. The windows let the light pour in, though darkness would have been preferred. Nearly a hundred men were walking in circles, hugging themselves, leaning their heads against the walls, sitting in the corners, and only a small handful congregated and interacted with one another. There were a few metal chairs, three rickety tables, and one bedbug-infested davenport. The tables usually held a few boxes of mismatched puzzles, several checker boards, tattered newspapers, and outdated magazines.

The night-shift staff gave Christine’s day-shift attendants a rundown of how their night had gone. Todd Adkins, the most experienced attendant, listened carefully to what the other attendants said. A loud crash came from the far right corner of the day room and the attendants jumped into action. Christine couldn’t see what the problem was in the sea of bodies but knew Adkins could handle it.

What would she have done in her first month as an official nurse in Ward 71 if it hadn’t been for Adkins? Of course, Christine wasn’t alone. Nurse Minton was the experienced nurse in her ward. How the two of them managed to keep track of over a hundred men with only two aides, she didn’t know.

Christine said good morning to a few of the nearby patients. None of them even looked in her direction, except for Floyd, the only mentally retarded mongol patient in their ward. He was secretly her favorite patient. It was one thing to study Dr. John Langdon Down’s work, which clinically described the syndrome in the mid-1800s, but to interact and observe Floyd was far better than learning from a textbook. He was sensitive, funny, and by far smarter than anyone gave him credit for. He bore no resemblance to the term mongoloid idiot used to describe his condition.

Floyd’s small, almond-shaped eyes, like slits in his puffy face, sparkled. He smiled at her, with more gums than teeth, and then returned to tapping two old checker pieces together. She patted his head as she passed him. Christine walked over to the office in the corner of the room where she would prepare to hand out the morning round of medications.

“We had to restrain Rodney a few hours after our shift started. He went after Floyd.” Millicent Smythe, one of the ward’s night-shift nurses, was writing in the patient logbook in the office. Her lips were pasty and unpainted, though twelve hours ago they’d been as red as Christine’s. Dark circles framed her brown eyes and her voice carried a hint of exhaustion.

“What? Floyd? He wouldn’t hurt a flea.” Christine said.

“Rodney said that Floyd was cussing at him. Rodney had all of them riled up—acting like the big cheese. It put a wrench in the whole night. Mr. Pricket even had a difficult time with him.”

Mr. Pricket was one of the oldest and most experienced attendants in all of Hudson River. Surely Rodney’s latest outburst would finally get him transferred to Ryan Hall, where the truly violent and disturbed patients were kept.

“I know what you’re thinking.” Millicent looked over at her and raised a dark brown eyebrow. “Ryan Hall.”

“Aren’t you?”

The other nurse shrugged. “They are even more crowded than we are and there are injuries weekly—both the patients and the staff. If anyone needs more help instead of more patients, it’s them.”

Just before Millicent left she called over her shoulder. “Have an attendant check on Wayne and Sonny when you get a minute. Wayne was agitated last night. Oh, and the laundry is behind—again.”

Christine nodded and hustled to get started handing out medications. The patients who were able lined up for their medications, which she handed through the open Dutch door. The attendants helped the less competent patients line up. She took a tray of medications out to the remaining patients who weren’t able to form a line or were bedridden. This took some time, since each had to drink down the medications in front of her so she could check inside their mouths—under their tongues and in the pockets of their cheeks.

When she was nearly half through with administering the medications, the attendants began taking the patients in shifts to the cafeteria to eat breakfast. When a patient in the other hall needed an unscheduled electroconvulsive therapy, often referred to as shock therapy, she was pulled in to assist since Nurse Minton was busy with an ill patient who had pulled his IV from his arm.

When she finally returned to the corner office in the day room her logbook was still open. Quickly Christine documented the lethargy of one patient she’d noticed earlier in the day and the aggressiveness of another. She reviewed the schedule for the rest of the day: more shock therapy, hydrotherapy for calming a few patients, and numerous catheterizations for the patients who refused to use the toilet. How would she keep up with it all?

She didn’t have time to dwell and carefully picked up the tray of medications she needed to finish. Christine was only a step out of the office when Wally approached her.

“Hey, nurse, have a smoke for me? Have a smoke for me?” Though his words were still slurred she was glad he had come out of his stupor from earlier that morning. “Come on, have a smoke for me?”

“Wally, you know I’m not going to give you any cigarettes.” She smiled at him. It was difficult to have a conversation with the men when they stood nude in front of her. She had trained herself to treat them as if they were fully clothed individuals and would look them directly in their eyes.

“Aw, come on, nurse, I know where you keep ’em,” he whispered loudly, stepping closer to her as she closed and locked the Dutch door. “What if I tell ya you’ve got some nice gams? You’re a real Queen ’o Sheba! Prettiest nurse here.”

“I don’t smoke, Wally.” It was only a half lie; she did smoke on occasion, but would never give a cigarette to a patient. “Now go back and play checkers before you get beat.”

“No one ever beats me. You know that. Never.” He repeated never over and over as he walked away.

The door to the day room swung open and hit the wall behind it. Adkins jogged in. His eyes were round and his face was as colorless as his starched attendant’s jacket.

“Nurse Freeman,” he said, breathless and shaky.

“What is it?” She’d never seen Adkins rattled before.

“I went to take some breakfast to Wayne and Sonny.”

“Just now?” She sighed heavily. “Adkins, this isn’t like—”

“While you were in shock therapy I had to pull Rodney into solitary and this is the first chance I’ve—it doesn’t matter now.” Adkins breathed heavy and shook his head. He stopped long enough to look into Christine’s eyes. “Wayne and Sonny are dead.”

“Dead? What do you mean they’re dead? From influenza?” They’d been sequestered to a private room for contagion for the last forty-eight hours.

He shook his head and grabbed her arm, making the small cups of pills on her tray rattle. “Froze to death.”

Numbness fixed her where she stood. Christine wasn’t sure she would be able to move from that spot. Had she heard him properly? It was her fault. She should’ve sent Adkins to check on them as soon as Millicent mentioned it. How long had it been since they’d been checked on? Her heart bemoaned that she had not insisted Adkins or even an attendant from Minton’s hall check on them immediately. She took a deep breath and the stench of guilt filled her lungs.

“Nurse Freeman?” His grip tightened on her arm.

“Yes.” She returned to the corner office behind her and calmly put the tray of meds on the counter. Then, with Adkins on her heels, she jogged to the last room in the hall.

Christine pushed her way through the crowd of patients gawking at the unclothed bodies that lay frozen. She wrapped her arms around herself, partly for warmth and partly for a sense of security. Her breath puffed white as her breathing quickened. Snow piled in small mounds on the floor and the walls were frosted around the two sets of open windows.

“Get everyone out,” she said rigidly to Adkins, who obeyed immediately.

Once the room was empty she had Adkins call for the administrator, Jolene Phancock. Christine also wanted to make sure Minton had heard the news. Once the two veteran staff members arrived they could instruct her on what to do next. Perhaps all that needed to be done was to call the morgue on the grounds to come pick the bodies up. They would hand them over to the state and have them buried in some unmarked plot for no one to grieve over.

“Good morning, Nurse Freeman,” Ms. Phancock said in an even and pleasant voice as she walked in. She was too friendly not to give a proper greeting, but her voice carried the bitterness of the morning’s events.

“Not a very good morning, unfortunately.” Christine tiptoed around the snow to the open windows and closed them. “Wayne is—was—always opening windows. We should’ve found a way to bolt the windows shut in here. I never thought this could happen. I feel responsible.”

Like a hollow cavern, Christine’s voice echoed in her own ears. Reality and dream crossed each other and she wasn’t sure what was true anymore. Wayne’s naked body, in the fetal position, was blue, and his bedsores were flaky. A shudder shook her body. Sonny, also blue, was long and skinny, and his toes were curled. He lay flat otherwise and had not even curled around himself to conserve heat. Guilt filled her empty heart.

She picked up Sonny’s chalk and slate on the floor next to his bed. As a young boy, deaf and dumb, he was sent to the Children’s Ward. There he’d been taught to write a few simple words in order to communicate. She blinked back hot tears when she saw what was scratched onto the slate.

Cold.

“Let me assure you that you are not to blame.” Ms. Phancock released such a heavy sigh Christine could feel the weight of it around her. The administrator made a fist with her hand and pursed her lips.

“Ma’am?” She laid the slate back down on the frozen floor.

“We need more workers.” Ms. Phancock’s fist pulsed up and down with each word. “You and the rest of the staff cannot possibly do more than you already are.”

Christine agreed, of course, as she looked at the tragedy before her.

She found herself sorry that Sonny’s nakedness was so visible, more than Wayne’s. Of course, they often had more naked patients than clothed ones. Keeping patients clothed was difficult if they were incontinent or when they displayed erratic behavior. But this time it seemed worse. He wasn’t just asleep or behaving dangerously. He was a human being who was lying naked in front of everyone coming in or near the room. She untied her apron and draped it over his lower body.

“What are you doing?” Nurse Minton asked as she strode in. Christine looked up at the older nurse. Her hair was already coming out of her severe bun, as if she’d been working all day instead of only a few hours.

“He deserves some dignity.” Christine turned to her superior.

“Thank you, Nurse Freeman,” Ms. Phancock said. “You’re right.”

Nurse Minton remained quiet.

“Can we tell the state what’s happening here? Maybe they will find a way to get us the help we need.”

“That sounds about as likely as a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.” Ms. Phancock sighed as she spoke. She patted Christine on the shoulder and told her that Gibson from the morgue would be there soon, then she left.

The two nurses remained in the room, silently together for several pregnant moments.

“Did you record Rodney’s insulin shock therapy today?” Nurse Minton finally broke the quiet.

“Nurse Minton, we have a real tragedy here, and you want to talk about insulin treatment?”

“We are nurses, Freeman. This is our job.” Her voice came out harshly, and even the old, jaded nurse seemed to realize it and cleared her throat. “I’ve been around long enough to know this is part of the job—though terrible, I understand. I also know that we have to keep the ward running regardless; otherwise another tragedy will be right around the corner.”

Christine nodded. Minton was right. She turned toward the older nurse and stifled a loud sigh. “Yes, Rodney got his insulin treatment.”

“Did his anxiety and aggressiveness subside? I was dealing with the other hall and haven’t checked on him yet.”

“Yes, ma’am.” Subsided was putting it mildly. Rodney had gone into a coma from the massive dose of insulin. He had lost all control several hours earlier when the doctor had come to see him about his outburst the night before. Like a frayed rope under too much strain, he snapped. “Tonic-clonic seizures continued for several minutes post therapy. He’s being observed for any aftershocks now.”

“Fine.” Nurse Minton looked at Christine out of the bottoms of her eyes, with her chin up and nose in the air. The older nurse was no taller than the younger, but looked down at her in any way she could find. Tall women were typically placed on men’s wards with the expectation that they would be able to better handle the larger male patients.

“Dr. Franklin has a standing order of barbital for him. If he wakes up agitated I will administer it. Dr. Franklin said to keep him in the restraints until he returns.” The use of the sleeping drug was a mainstay in the hospital.

“I’ll leave you to deal with Gibson and the morgue; I’ll get back to the patients. We still have a full day.” The older nurse started walking out of the room.

“Nurse Minton, don’t you wish there was more we could do? You’ve been here for years and I’m new, but I already feel so helpless.”

“Adkins said you were idealistic.” The older nurse’s mouth curled into an unfriendly and mocking smile. “Idealism doesn’t work in a place like this. Look around, Freeman. This facility is its own town, with its own community. You know that. Do you think the state is going to listen to you, a woman just barely a nurse? Your very meals depend on the garden the patients maintain and their harvest and canning in the fall. Why do you think it’s like that?” She paused for a minuscule moment, appearing not to want an answer from Christine. “Because no one wants to bother with the patients. No one wants to even believe they exist, including the families that drop them off. They want to go on with their nice simple lives behind their picket fences and pretend this beautiful building isn’t more prison than hospital. Besides, even if we had more clothing for the patients, what we really need are workers. There’s just too many patients and not enough of us.”

They’d been over capacity for a long time without any help in sight. The war had taken so many of their staff away while an excessive number of patients poured in—some of them soldiers returning from the war and unable to cope.

Without another word, Nurse Minton walked away but turned back after several steps.

“Adkins says you sing hymns to your patients.” One of her eyebrows arched and a crooked smirk shifted across her lips.

“I think it helps their nerves,” she said pushing up her glasses though they had not slipped down her nose.

“Sing all you want, as long as you’re getting your work finished.” The nurse turned and walked away.

“S’cuse me, ma’am,” a deep voice said a few moments later.

Christine’s eyes caught Gibson’s. He was holding one end of a canvas stretcher and a younger man held the other. Gibson was a tall, brawny colored man with a voice that was gravelly yet still somehow kind. His cottony hair and eyebrows reminded Christine of summer clouds. His eyes, on the other hand, haunted her.

Gibson’s job was to gather the deceased and take them across the hospital grounds to the morgue. If warranted, a doctor would perform an autopsy before the patient was prepared for burial. In that brief moment she returned to a hot August day when she had observed an autopsy. Half her class fainted. Christine nearly had herself. The odor, sight, and sounds, mixed with the humidity, made her fantasize about running away from the school.

Now, in the frozen days of winter, Christine wanted to pretend she was somewhere else. She shuffled awkwardly back toward the wall near the windows, her knees locked. She could not watch them take the bodies away, not like this. Without a word, she pushed past them and left the room. She ran to the opposite end of the hall and leaned against the stairwell door.

http://books.simonandschuster.ca/Promise-to-Cherish/Elizabeth-Byler-Younts/Promise-of-Sunrise/9781476735030#excerpt

Best First Book finalist, 2014 RITA Awards ~ Elizabeth Byler Younts ~ Promise to Return, Book 1, Promise of Sunrise series

|

| The Promise of Sunrise Series, Book 1 |

An interview with Carrie Turansky, Author of The Daughter of Highland Hall

An interview with Carrie Turansky, Author of The Daughter of Highland Hall