In March of 1957, much in love, with all that they owned in suitcases, a young couple from the Netherlands boarded a ship to cross the Atlantic for an unknown future in Canada, both leaving behind the events of what the Great War had inflicted on them as children.

In March of 1957, much in love, with all that they owned in suitcases, a young couple from the Netherlands boarded a ship to cross the Atlantic for an unknown future in Canada, both leaving behind the events of what the Great War had inflicted on them as children.As a small girl, she watched German soldiers take away her father for hiding a Jew in their house. Halfway across the world, at about the same time, Japanese soldiers forced the boy’s father and older brothers onto the flatbed of a truck that left the boy and the other siblings behind.

In Holland, the girl’s father eventually returned, but she endured the remainder of the Nazi occupation without her mother, who died from pneumonia. In the Dutch East Indies, the boy’s father did not return, a victim of the brutal conditions of forced labor during the building of the infamous Burma railway, and the boy spent his war years with his mother and remaining siblings barely surviving a series of concentration camps.

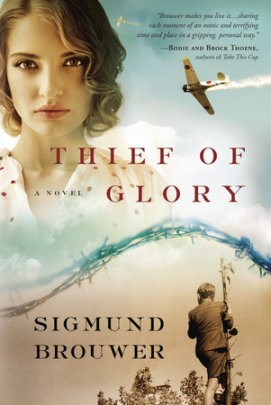

All these years later, at the time of the writing of this novel, they are still together, still much in love. They have six children, fifteen grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren. In the truest sense, this novel was inspired by that young couple—by stories of their childhoods and by how they lived and loved since that Atlantic crossing—my parents Willem and Gerda. Because of their example, it was not difficult to imagine another decades-long journey in Thief of Glory, where Jeremiah and Laura share a similar enduring love. --author Sigmund Brouwer

Devastation of a people and a home, Jeremiah Prins looks back on his life as a young boy to manhood in a time set apart from the sound of birdsong, of children playing in the streets, of mothers calling in the marketplace. Gone, all of it gone. Day-to-day life as it had been known was no more.

There was Laura. A love so profound from the very beginning. Laura, the thought of her kept me going. Change to change, movement to movement. A lifetime ago.

A boy coming of age in a time of war...the love that inspires him to survive.

For ten-year-old Jeremiah Prins, the life of privilege as the son of a school headmaster in the Dutch East Indies comes crashing to a halt in 1942 after the Japanese Imperialist invasion of the Southeast Pacific. Jeremiah takes on the responsibility of caring for his younger siblings when his father and older stepbrothers are separated from the rest of the family, and he is surprised by what life in the camp reveals about a woman he barely knows—his frail, troubled mother.

Amidst starvation, brutality, sacrifice and generosity, Jeremiah draws on all of his courage and cunning to fill in the gap for his mother. Life in the camps is made more tolerable as Jeremiah’s boyhood infatuation with his close friend Laura deepens into a friendship from which they both draw strength.

When the darkest sides of humanity threaten to overwhelm Jeremiah and Laura, they reach for God's light and grace, shining through His people. Time and war will test their fortitude, and the only thing that will bring them safely to the other side is the most enduring bond of all.

As we are rounded up to be taken to one of the Jappenkamps by the Japanese soldiers in the fall of 1942, I returned to our house to take the mattress from our parents' bed. I am amazed to see for the first time, papers lining the walls with sketches of our days, drawn by my mother in her haze of mental disparity. Beautiful. They are so accurate. She does see us.

Then another sketch caught my eye. It was me, with my mother. We were holding hands, and her dress swirled at her ankles as if the wind were flirting with her. She and I never held hands. In this sketch she also had a smile on her face that I'd never seen before, and nothing about my eyes in that sketch looked as intense and cold as the eyes I sometimes saw in a mirror. Instead, happiness shone from my face.I have read The Butterfly and the Violin by Kristy Cambron this year, and accounts of Corrie ten Boom's concentration camp writings, and Anne Frank, previously. Thief of Glory brings forth historical happenings not readily revealed in such detail. Written in first person narrative, this story embodies thoughts and feelings with the intensity of being there. The strength of the women as they bond together as best they can, children being exposed to horrors beyond their years.

--Thief of Glory, 57.

Thief of Glory is very well written by author Sigmund Brouwer, carrying the wit and survival tactics of Jeremiah, known as Jemmy to his young brother, Pietje. Caring and looking out for his other siblings too, Nikki and Aniek, Jeremiah becomes the overseer of his family in places his mother is unable to, especially when she retreats into her unknown world.

The story is written in a remembering stage, looking back. Such memories would be embedded in the heart and soul. Not wanting his daughter, Rachel, to be entangled in what Jeremiah had endured, he agrees to tell her the story ~ revealed through his detailed writings to be read after his passing. Such is love, to protect. Reconciliation of hearts beginning, clear the way to understanding.

War atrocities in each generation portrayed in daily putting one foot before the other to survive. This story will be remembered.

Sigmund’s father talks about his boyhood in an internment camp in the Dutch East Indies

|

| Photo © Reba Baskett |

***Thank you to Blogging for Books for sending me a copy of Sigmund Brouwer's Thief of Glory to review. This review was written in my own words. No other compensation was received.***

Enjoy this SneakPeek of Thief of Glory written by Sigmund Brouwer ~

ONE

Journal 1—Dutch East IndiesA banyan tree begins when its seeds germinate in the crevices of a host tree. It sends to the ground tendrils that become prop roots with enough room for children to crawl beneath, prop roots that grow into thick, woody trunks and make it look like the tree is standing above the ground. The roots, given time, look no different than the tree it has begun to strangle. Eventually, when the original support tree dies and rots, the banyan develops a hollow central core.

In a kampong—village—on the island of Java, in the then-called Dutch East Indies, stood such a banyan tree almost two hundred years old. On foggy evenings, even adults avoided passing by its ghostly silhouette, but on the morning of my tenth birthday, sunlight filtered through a sticky haze after a monsoon, giving everything a glow of tranquil beauty, where an event beneath the branches, as seemingly inconsequential as a banyan seed taking root in the bark of an unsuspecting tree, began the journey that has taken me some three score and ten years to complete.

It was market day, and as a special privilege to me, Mother had left my younger brother and twin sisters in the care of our servants. In the early morning, before the tropical heat could slow our progress, she and I journeyed on back of the white horse she was so proud of, past the manicured grounds of our handsome home and along the tributary where my siblings and I often played. Farther down, the small river emptied into the busy port of Semarang. While it was not a school day, my father—the headmaster—and my older half brothers were supervising the maintenance of the building where of all of the blond-haired children experienced the exclusive Dutch education system.

As we passed, Indonesian peasants bowed and smiled at us. Ahead, shimmers of heat rose from the uneven cobblestones that formed the village square. Vibrant hues of Javanese batik fabrics, with their localized patterns of flowers and animals and folklore as familiar to me as my marbles, peeked from market stalls. I breathed in the smell of cinnamon and cardamom and curry powders mixed with the scents of fried foods and ripe mangoes and lychees.

I was a tiny king that morning, continuously shaking off my mother’s attempts to grasp my hand. She had already purchased spices from the old man at one of the Chinese stalls. He had risen beyond his status as a singkeh, an impoverished immigrant laborer from the southern provinces of China, this elevation signaled by his right thumbnail, which was at least two inches long and fit in a curving, encasing sheath with elaborate painted decorations. He kept it prominently displayed with his hands resting in his lap, a clear message that he held a privileged position and did not need to work with his hands. I’d long stopped being fascinated by this and was impatient to be moving, just as I’d long stopped being fascinated by his plump wife in a colorful long dress as she flicked the beads on her abacus to calculate prices with infallible accuracy.

I pulled away to help an older Dutch woman who was bartering with an Indonesian baker. She had not noticed that bank notes had fallen from her purse. I retrieved them for her but was in no mood for effusive thanks, partly because I thought it ridiculous to thank me for not stealing, but mainly because I knew what the other boys my age were doing at that moment. I needed to be on my way. With a quick Dag, mevrouw—Good day, madam—I bolted toward the banyan, giving no heed to my mother’s command to return.

For there, with potential loot placed in a wide chalked circle, were fresh victims. I might not have been allowed to keep the marbles I won from my younger siblings, but these Dutch boys were fair game. I slowed to an amble of pretended casualness as I neared, whistling and looking properly sharp in white shorts and a white linen shirt that had been hand pressed by Indonesian servants. I put on a show of indifference that I’d perfected and that served me well my whole life. Then I stopped when I saw her, all my apparent apathy instantly vanquished.

Laura.

As an old man, I can attest to the power of love at first sight. I can attest that the memory of a moment can endure—and haunt—for a lifetime. There are so many other moments slipping away from me, but this one remains.

Laura.

What is rarely, if ever, mentioned by poets is that hatred can have the same power, for that was the same moment that I first saw him. The impact of that memory has never waned either. This, too, remains as layers of my life slip away like peeling skin.

Georgie.

I had no foreshadowing, of course, that the last few steps toward the shade beneath those glossy leaves would eventually send me into the holding cell of a Washington, DC police station where, at age eighty-one, I faced the lawyer—also my daughter and only child—who refused to secure my release until I promised to tell her the events of my journey there.

All these years later, across from her in that holding cell, I knew my daughter demanded this because she craved to make sense of a lifetime in the cold shade of my hollowness, for the span of decades since that marble game had withered me, the tendrils of my vanities and deceptions and self-deceptions long grown into strangling prop roots. Even so, as I agreed to my daughter’s terms, I maintained my emotional distance and made no mention that I intended to have this story delivered to her after my death.

Such, too, is the power of shame.

TWO

Laura.

Beneath the banyan, a heart-stopping longing overwhelmed me at the glimpse of her face and shy smile. It was romantic love in the purest sense, uncluttered by any notion of physical desire, for I was ten, much too young to know how lust complicates the matters of the human race.

The sensation was utterly new to me. But it was not without context. At night, by oil lamps screened to keep moths from the flame, I had three times read Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott, the Dutch translation by Gerard Keller. As soon as the last page was finished, I would turn to page one of chapter one. I had just started it for the fourth time. Thus I’d been immersed in chivalry at its finest and here, finally, was proof that the love I’d read about in the story also existed in real life.

I was lost, first, in her eyes—the calmest of blue. She looked away, then back again. I felt like I could only breathe from the top of my lungs in shallow gasps. Her hair, thick and blond and curled, rested upon her shoulders. She wore a light-blue dress, tied at the waist with a wide bow, with a yellow butterfly brooch on her right shoulder. She stole away from me any sense of sound except for a universal harmony that I hadn’t known existed. So as the nine-year-old Laura Jansen bequeathed upon me a radiant gaze, I became Ivanhoe, and she the beautiful Lady Rowena. Standing at the edge of the chalked circle, I was instantly and irrevocably determined that nothing would stop me from becoming champion of the day, earning the right to bestow upon her the honor of Queen of the Tournament.

As I was to discover, it was Laura’s third day in-country and her first visit to the village. This meant I was as much a stranger to her as any boy could be, but the emotions that overwhelmed her, which she recounted to me years later, were as much a mystery to her young soul as my emotions were to mine.

I would shortly discover that Laura had accompanied her oma— grandmother—on the voyage from the Netherlands. Her oom Gert—uncle Gert—worked for the Dutch Shell Oil Company as a refinery engineer, and his wife had recently died from pneumonia. Laura and her oma had come to help Gert and his large family through the difficult situation.

That morning I surveyed my opponents gathered around her, a motley bunch of boys I’d vanquished one way or another at events where Dutch families gathered to celebrate a holiday or other special occasion. From marble games to subsequent fistfights that resulted from marble games, the fathers monitored our battles but wisely kept them as hidden from the matriarchs as we did. I knew all of these boys. Except one.

As the other boys took involuntary steps backward in deference to my established reign, I felt goose bumps run up my spine. The parting of this group had revealed a boy at the center whom I’d never seen before. He was kneeling, with a marble held in shooting position on top of the thumbnail of his left hand, edge of the thumb curled beneath index finger, ready to flick. Left hand.

The marble I noticed too. For good reason. It was an onionskin, purple and white, with a transparent core. The swirls were twisted counterclockwise and that made it even more of a rarity. Inside the chalked circle was an X formed by two lines of twelve marbles. At a glance I could tell none were worth the risk of losing the onionskin. Without doubt, stupidity was not part of this boy’s nature, so either he was very good or he came from wealth that allowed him to not care about the worth of the onionskin.

When he stood, it was obvious that he had two inches on me, and a lot of extra bulk. His arched eyebrow matched my own. Dark hair to my blond. Khaki pants and tousled shirt to my pressed-linen shorts and shirt. Wealth, most likely, against the limited salary of my father’s headmaster position.

I did not ask him for his name, but I would soon learn it was Georgie Smith. He was American. Son of the man sent to oversee the refinery where Laura’s uncle worked as an engineer. He’d arrived by the same ship that had carried Laura and her oma.

I doubt Georgie’s conscious brain registered the deferential movements of the other boys, but his animal instinct would not have failed to miss it. Or the reasons for it. Like an electrical current generated by rising tension, hatred crackled between us. I believe that had we each been armed with clubs, we would have charged forward without hesitation at the slightest of provocations.

This unspoken hatred was established in the time it took to lock eyes. With effort, I pretended not to see him as I moved to the edge of the chalked circle and squatted. I could feel the burn of his gaze on my right shoulder, as I imagined the caressing smile of Laura warming my left shoulder. It was no accident I had chosen a position that placed me between them.

“Who is next?” I asked, keeping my eyes on the marbles.

“We’ve been saving a place for you,” Timothy said. He was eight years old, and a snot-nosed, obsequious toad, but his answer established that I was leader.

Still watching and waiting for the onionskin to enter the circle, I fumbled with my belt. I always carried two small pouches of marbles tied to my belt and tucked inside my shorts.

“He’s not playing,” Georgie said.

This earned a respectful gasp from the other boys.

I turned my head to give him a direct stare.

“He wasn’t here when the game started so he can’t be part of it,” Georgie continued, speaking of me in the third person as if I were not there in front of him. “He should run back to his mother and she can inspect his pretty clothes so she can make sure he hasn’t smudged himself or wet his pants.”

He smirked and waited for my response.

THREE

With Georgie only a few steps away, every nerve of mine tingled; I was intensely aware of the full challenge he had thrown at me and of the significance of how I responded. Not only in Laura’s eyes, which was what mattered most, but in how it might change my status among my peers. Over the years, my role in the pack of local boys had been clearly established. I could roam through their territory as I pleased with a well-earned diplomatic pass. Preteen boys do not articulate this, but our genetic imprint demands a pecking order. It unfolds whenever boys who are old enough to walk grasp at toys in the hands of other boys.

I looked away from Georgie.

“What is your name?” I asked Laura, for of course, I didn’t know it then. What I believed already, without doubt, was that she was destined to be my lifelong love.

“Laura,” she answered. “My name is Laura Jansen.”

Laura.

“Her father works for my father,” the American boy said. His Dutch had an accent to it, but, I had to admit, he appeared to be able to speak it fluently. “At the refinery.”

At this, I saw the slightest flinch on Laura’s face.

The power of the human brain to read mere flickers of body language, the tiniest of voice inflections, and the subtly of eye movement, all to draw instant and subconscious conclusions beyond the reach of studied logic, should never be underestimated. Children learn early to assess a parent’s mood and react accordingly. Because I was the only one seeing her face—absorbed in it as I was, despite the threat from Georgie—only I understood I had just won the war against the boy I already hated. What remained, however, were the battles.

“Hello, Laura,” I said, as if only she and I shared the shade of the banyan, for in a way, of course, that was true. “My name is Jeremiah Prins. Are you here at the market with your parents?”

“I was told to watch her,” my enemy said, giving more evidence that she was someone he wanted to impress. “She came with me.”

Laura flinched again, and those deep-blue eyes lost some calm.

“I came with my oma to the market,” Laura answered. “Georgie asked to join us because he was bored.”

She finally glanced at him. “I don’t need anyone to watch over me.”

He understood how clearly she was making her choice known, and his body went rigid.

“This seems to be an unpleasant situation,” I told Laura, echoing how I believed a knight like Ivanhoe would speak. “Would it be all right if I took you to your oma? The market is confusing, and if it’s your first time, I can make it easier for you.”

I was rewarded with the smile. I reached for her hand, and she took a step toward me. Away from Georgie.

“Coward,” Georgie said with full sneer.

“Oh,” I said, having fully expected and anticipated that he would not let me walk away without a challenge. I did not want to walk away. “Coward? Afraid of what?”

“A fight,” he said.

I was disappointed that my hand had not reached Laura’s and that I needed to turn to face him before I could feel the touch of her fingers against mine.

“Who wants to fight me?” I asked. Already I could tell that I would be able to twist and skewer him with words.

He grunted with frustration. “I just called you a momma’s boy.”

“Actually,” I said, “you suggested that she inspect my clothing. I don’t need help with that. It’s rather silly to suggest that a boy our age needs help to know if he’s wet his pants.”

I paused. Timing is everything. “Unless it’s happened to you.”

That earned laughter. Like an arrow, it had the desired effect on Georgie, who clenched his fists.

“I was insulting you,” he said. “Are you that stupid? It should make you want to fight me. Unless you are chicken.”

“If you want to fight,” I said, “why don’t you just ask?”

This was entertaining for the other boys. I knew it and enjoyed it.

Georgie spit in my direction. “I’m going to pound you so bad you’ll bleed from your ears.”

“How can that be if we don’t fight?” I asked.

“See. Chicken.”

“That doesn’t sound like a question to me,” I said. I turned to Laura, who had giggled when the other boys laughed. “It will be embarrassing to him if I need to explain what a question is. Let’s find your oma.”

Georgie began to gurgle. Such is the power of deliberate insouciance.

“Come on,” Georgie half shouted. “Let’s fight.”

“All you need to do is ask,” I said. “Is that so difficult to understand?”

Georgie had no idea how easily I had taken control of the situation. But then, I had no idea of the extent of his cruelty and preference for inflicting pain. Yet.

Before Georgie could do what I was essentially commanding him to do, Klaus Akkermans stepped onto our stage. Klaus was one of the older boys, almost thirteen. Slicked-back hair and a gap between his front teeth. Twenty pounds heavier than I. During our fistfight a few months ago, he’d hit me so hard in the belly that I had thrown up on his feet.

“I wouldn’t ask,” Klaus told Georgie. “Jeremiah doesn’t lose fights.”

“He’s fast,” Timmie the Toad said. If Timmie was publicly choosing sides this early, then the invisible opinion of the group had shifted in my favor. “When Jeremiah was four, a cobra crawled into his bed. He grabbed it by the neck and went into the kitchen and cut off its head. Right, Jeremiah?”

I shrugged. Truth was, I couldn’t remember it, and family stories, I’m sure, have a way of getting exaggerated with each retell.

“It’s not that he’s fast,” Klaus told Georgie. “Although he is. He just doesn’t lose fights.”

Georgie looked back and forth between Klaus and Timmie the Toad, trying to evaluate this new information.

“Not even the teenagers fight him,” said Alfie Devroome. He had the slightest of a clubfoot on his left side. When we chose teams for races, I always made sure he was my second or third pick. First would look too patronizing.

“He can’t win fights against teenagers,” Georgie said. “Look at how little he is.”

Klaus shook his head. “Nobody said he wins fights. He just doesn’t lose them. We’ve just about all had our turns against Jeremiah.” He glanced around, then looked back at Georgie. “When I fought him, I hit him so many times my hands hurt, and he was bleeding everywhere. He even threw up on my shoes. It only ended because I had to tell him I was tired.”

Klaus put his hands on his hips. “Like I said, he didn’t win. But he didn’t lose. Older boys know they would to have to kill him to end the fight, so they leave him alone.”

“You also lost some teeth,” Timmie the Toad reminded Klaus. “He did hit you a couple of good ones.”

“I’ve told you,” Klaus answered. “Those were loose anyway.”

“And don’t forget about how he whacked a sow in the head with a hammer and killed it,” added Simon Leeuwenhoek, a chubby kid and the only one in the bunch I had not fought. Simon was too good-natured for that. And his parents were rich so he didn’t care much about how many marbles he lost. “Jeremiah was only nine.”

This I did remember.

“I didn’t kill it,” I said. “I just hit it once. Because it was attacking me.”

The previous summer, we had been visiting a plantation of a family whose children attended my father’s school. I had ignored my mother’s warning to stay away from the sow and piglets inside the pen, and the sow had torn a chunk out of my left calf as I was scrambling to climb out.

As happened when I was threatened physically, a switch inside of me had flipped on and numbed my body to anything except cold and calculating rage, accelerated by all the benefits of accompanying adrenaline. It means that when I fight, I still have clarity of thought, and I’m aware that this is a rarity of inheritance in which I can and should take no pride.

I’d returned to the pigpen with a hammer found in a nearby shed. When the sow charged me again, I had brought it down with both hands and solidly struck it between the eyes. Knocked it cold. The fathers had not chosen sides, but an argument escalated between the mothers. Mine made the accusation that dangerous animals should be controlled, and the other mother suggested that I, not the sow, was the dangerous animal and that I was a bad example to the other children. Even though the sow only swayed sideways when it got up and walked, and I needed thirty stitches to pull together the ragged skin and muscle of my calf, the other mother insisted I was to blame and we hadn’t been invited back. I’d promised not to do something like that again because it had upset my mother. She spent hours alone in a dark, cool room when things upset her. Her spells frightened all of us children in the family.

“I’m not scared,” Georgie told our audience. To his credit, he didn’t sound scared. He wanted to fight me as badly as I wanted to fight him.

“Then ask,” I said. I could sense the coldness at the edge of my gut, and I wanted to feel his nose crack against my fist. “I’m not allowed to ask for a fight. And I’m not allowed to take the first swing.”

Those were my father’s rules. He said Jesus had not been one to fight. However, Father allowed that it would be impractical to live without any kind of self-defense. His corollary advice was that if you had to strike back, do it far out of proportion to the attack because that will discourage future attacks. This counsel had a certain kind of logic if you were hoping to be able to settle back to living like Jesus, but Georgie, as I would learn in the coming years, was just as determined to escalate his hatred against me as I was against him.

There was silence as Georgie realized that asking me to fight would be his first defeat, but he had no choice.

“Will you fight me?” Georgie finally asked. His tone suggested that he was stunned to find himself in the position of a supplicant, and still trying to figure out how it had happened.

“Yes,” I said. “But first I’d like to ask Laura if she will leave and shop with her oma in the market. This will be ugly.”

“I’m not afraid of ugly,” she said. “I’m not a sissy.”

A slight flicker of indignation crossed her face. This girl, it was obvious, did not like being told what to do. That simply made her Dutch. I recovered with an immediate explanation.

“I just don’t want you to have to lie about it when the mothers ask later,” I said. “If you don’t see anything, you won’t have to lie. It’s a way of protecting me.”

Lots of unspoken assumptions in there, all favoring me, like the assumption that she would want to protect me, even enough to lie for me. What was artful was that nothing in my request suggested she should protect Georgie, even though his father was the boss of her father.

“Oh,” she said to me. “Since you asked. Yes.”

It hadn’t occurred to me that she would give any other answer.

I turned to Georgie. “We’re going to need to find a place where mothers can’t see us. Just past the village there’s a stream and a small fenced pasture for goats. The boys will take you there and I’ll have both pieces of rope. I know where I can find some in the market.”

“Rope?” Georgie would have been inhuman not to ask.

“I don’t want you running away,” I said. The cold inside me was mushrooming, and horrible as it is to confess, I was savoring the sensation and the chance to inflict punishment on him. I had no concern about the punishment I’d have to endure for that chance. “The pasture is fenced. We tie our own belts to a fence post with enough slack in each rope that we can reach each other. Once we are tied to the fence posts, one won’t be able to run away from the other. Then we fight.”

I grinned at the taller and broader boy in front of me.

“Unless,” I said, “you are chicken.”

Sigmund Brouwer, Thief of Glory WaterBrook Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company, © 2014.

No comments:

Post a Comment