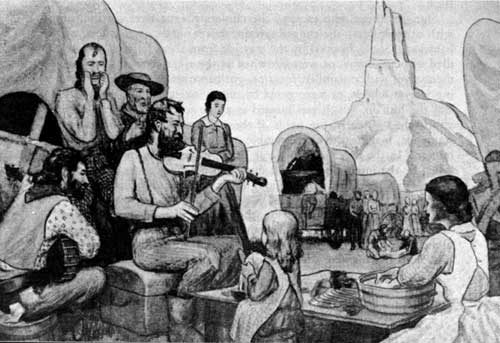

Virgilia had so little time to herself she wasn't sure she knew how to be frivolous, but she liked the idea of trying to find something that mattered that she could take. She'd be sure to take the pewter icing knife. Surely she'd be able to bake cakes.Going West from your Missouri home, how would you manage? Would you have a particular keepsake that is a part of you? As the deciding goes on, what would be left behind? A memory, a hope, a love not known?

--This Road We Traveled, 66.

Opening up the new country, Orus Brown returned to Missouri to encourage others to join the settlement he is now part of in Oregon. Engaging others in St. Charles to follow the wide open spaces of 640 acres granted ~ all those with exception of his mother, Tabitha (Tabby) Moffat Brown. What would be behind his refusal to take her along?

1846, St. Charles, Missouri

Not to be detoured into sameness, Tabby goes to see her son, Manthano, as the youngest and separated part of her family a hundred miles away. Part of the deciding factor to travel to Oregon, she finds Orus has already been there to talk with him. The decision is hers to make now.

Eight months later, Oregon

Arriving finally at their destination, determined and agreeable to settle, Tabby begins anew the venture of her life. Where is she to choose to go? To nearer Salem, with her daughter Pherne and her family, or continuing on to the settlement of her son Orus? The arduous journey has brought changes and growth.

Enjoy this excerpt from Jane Kirkpatrick's novel, This Road We Traveled ~

Prologue

November 1846

Southern Oregon Trail

It was a land of timber, challenge, and trepidation, forcing struggles beyond any she had known, and she’d known many in her sixty-six years. But Tabitha Moffat Brown decided at that moment with wind and snow as companions in this dread that she would not let the last entry in her memoir read “Cold. Starving. Separated.” Instead she inhaled, patted her horse’s neck. The snow was as cold as a Vermont lake and threatening to cover them nearly as deep while she decided. She’d come this far, lived this long, surely this wasn’t the end God intended.

Get John back up on his horse. If she couldn’t, they’d both perish.

“John!”

The elderly man in his threadbare coat and faded vest sank to his knees. At least he hadn’t wandered off when he’d slid from his horse. His white hair lay wet and coiled at his neck beneath a rain-drenched hat. His shoulder bones stuck out like a scarecrow’s, sticks from lack of food and lost hope.

“You can’t stop, John. Not now. Not yet.” Wind whistled through the pines and her teeth chattered. “Captain!” She needed to sound harsh, but she nearly cried, his name stuck in the back of her throat. This good man, who these many months on the trail had become more than a brother-in-law, he had to live. He couldn’t die, not here, not now. “Captain! Get up. Save your ship.”

He looked up at her, eyes filled with recognition and resignation. “Go, Tabby. Save yourself.”

“Where would I go without you, John Brown? Fiddlesticks. You’re the captain. You can’t go down with your ship. I won’t allow it.”

“Ship?” His eyes took on a glaze. “But the barn is so warm. Can’t you smell the hay?”

Barn? Hay? Trees as high as heaven marked her view, shrubs thick and slowing as a nightmare clogged their path, and all she smelled was wet forest duff, starving horseflesh, and for the first time in her life that she could remember, fear.

Getting upset with him wouldn’t help. She wished she had her walking stick to poke at him. Her hands ached from cold despite her leather gloves. She could still feel the reins. That was good. What a pair they were: he, old and bent and hallucinating; she, old and lame and bordering on defeat. Her steadfast question, what do I control here, came upon her like an unspoken prayer. Love and do good. She must get him warm or he’d die.

With her skinny knees, she pushed her horse closer to where John slouched, all hope gone from him. Snow collected on his shoulders like moth-eaten epaulets. “John. Listen to me. Grab your cane. Pull yourself up. We’ll make camp. Over there, by that tree fall.” She pointed. “Come on now. Do it for the children. Do it for me.”

“Where are the children?” He stared up at her. “They’re here?”

She would have to slide off her horse and lead him to shelter herself. And if she failed, if her feet gave out, if she couldn’t bring him back from this tragic place with warmth and water and, yes, love, they’d both die and earn their wings in Oregon country. It was not what Tabitha Moffat Brown had in mind. And what she planned for, she could make happen. She always had . . . until now.

Part One

1

Tabby’s Plan

1845

St. Charles, Missouri

Tabitha Moffat Brown read the words aloud to Sarelia Lucia to see if she’d captured the rhythm and flow. “Feet or wings: well, feet, of course. As a practical matter we’re born with limbs, so they have a decided advantage over the wistfulness of wings. Oh, we’ll get our wings one day, but not on this earth, though I’ve met a few people who I often wondered about their spirit’s ability to rise higher than the rest of us in their goodness, your grandfather being one of those, dear Sarelia. Feet hold us up, help us see the world from a vantage point that keeps us from becoming self- centered—one of my many challenges, that self-centered portion. I guess the holding up too. I’ve had to use a cane or walking stick since I was a girl.”

“How did that happen, Gramo?” The nine-year-old child with the distinctive square jaw put the question to her.

“I’ll tell you about the occasion that brought that cane into my life and of the biggest challenges of my days . . . but not in this section. I know that walking stick is a part of my feet, it seems, evidence that I was not born with wings.” She winked at her granddaughter.

“When will you get to the good parts, where you tell of the greatest challenge of your life, Gramo? That’s what I want to hear.”

“I think this is a good start, don’t you?”

“Well . . .”

“Just you wait.”

Tabitha dipped her goose quill pen into the ink, then pierced the air with her weapon while she considered what to write next.

“Write the trouble stories down, Gramo. So I have them to read when I’m growed up.”

“When you’re grown up.”

“Yes, then. And I’ll write my stories for you.” A smile that lifted to her dark eyes followed. “I want to know when trouble found you and how you got out of it. That’ll help me when I get into trouble.”

“Will it? You won’t get into scrapes, will you?” Tabby grinned. “We’ll both sit and write for a bit.” The child agreed and followed her grandmother’s directions for paper and quill.

The writing down of things, the goings-on of affairs in this year of 1845, kept Tabby’s mind occupied while she waited for the second half of her life to begin. Tabby’s boys deplored studious exploits, which had always bothered her, so she wanted to nurture this grandchild—and all children’s interest in writing, reading, and arithmetic. So far, the remembering of days gone by had served another function: a way of organizing what her life was really about. She was of an age for such reflection, or so she’d been told.

Whenever her son Orus Brown returned from Oregon to their conclave in Missouri, she expected real ruminations about them all going west—or not. Perhaps in her pondering she’d discover whether she should go or stay, and more, why she was here on this earth at all, traveling roads from Connecticut southwest to Missouri and maybe all the way to the Pacific. Wasn’t wondering what purpose one had walking those roads of living a worthy pursuit? And there it was again: walking those roads. For her it always was a question of feet or wings.

Sarelia had gone home long ago, but Tabby had kept writing. Daylight soon washed out the lamplight in her St. Charles, Missouri, home, and she paused to stare across the landscape of scrub oak and butternut. Once they’d lived in the country, but now the former capital of Missouri spread out along the river, and Tabby’s home edged both city and country. A fox trip-tripped across the yard. Still, Tabby scratched away, stopping only when she needed to add water to the powder to make more ink. She’d have to replace the pen soon, too, but she had a good supply of those. Orus, her firstborn, saw to that, making her several dozen before he left for Oregon almost two years ago now. He was a good son. She prayed for his welfare and wondered anew at Lavina’s stamina managing all their children while they waited. Well, so was Manthano a good son, though he’d let himself be whisked away by that woman he fell in love with and rarely came to visit. Still, he was a week’s ride away. Children. She shook her head in wistfulness. Pherne, on the other hand, lived just down a path. And it was Pherne, her one and only daughter, who also urged her to write her autobiography. “Your personal story, Mama. How you and Papa met, where you lived, even the wisdom you garnered.”

Wisdom. She relied on memory to tell her story and memory proved a fickle thing. She supposed her daughter wanted her to write so she wouldn’t get into her daughter’s business. That happened with older folks sometimes when they lacked passions of their own. She wanted her daughter to know how much being with her and the children filled her days. Maybe not to let her know that despite her daughter’s stalwart efforts, she was lonely at times, muttering around in her cabin by herself, talking to Beatrice, her pet chicken, who followed her like a shadow. She was committed to not being a burden on her children. Oh, she helped a bit by teaching her grandchildren, but one couldn’t teach children all day long. Of course lessons commenced daily long, but the actual sitting on chairs, pens and ink in hand, minds and books open, that was education at its finest but couldn’t fill the day. The structure, the weaving of teacher and student so both discovered new things, that was the passion of her life, wasn’t it?

Still, she was intrigued by the idea of recalling and writing down ordinary events that had helped define her. Could memory bring back the scent of Dear Clark’s hair tonic or the feel of the tweed vest he wore, or the sight of his blue eyes that sparkled when he teased and preached? She’d last seen those eyes in life twenty-eight years ago. She had thought she couldn’t go on a day without him, but she’d done it nearly thirty years. What had first attracted her to the man? And how did she end up from a life in Stonington, Connecticut, begun in 1780, to a widow in Maryland, looking after her children and her own mother, and then on to Missouri in 1824 and still there in winter 1845? Was this where she’d die?

“‘A life that is worth writing at all, is worth writing minutely and truthfully.’ Longfellow.” She penned it in her memoir. This was a truth, but perhaps a little embellishment now and then wouldn’t hurt either. A story should be interesting after all.

~*~

His beard reached lower than his throat. Orus, Tabby’s oldest son, came to her cabin first. At least she assumed he had, as none of his children nor Pherne’s had rushed through the trees to tell her that he’d already been to Lavina’s or Virgil and Pherne’s place. It was midmorning, and her bleeding hearts drooped in the August heat.“I’m alive, Mother.” He removed his hat, and for a moment Tabby saw her deceased husband’s face pressed onto this younger version, the same height, nearly six feet tall, and the same dark hair, tender eyes.

“So you are, praise God.” She searched his brown eyes for the sparkle she remembered, reached to touch his cheek, saw above his scruffy beard a red-raised scar. “And the worse for wear, I’d say.”

“I’ll tell of all that later. I’m glad to see you among the living as well.”

“Come in. Don’t stand there shy.”

He laughed and entered, bending through her door. “Shyness is not something usually attached to my name.”

“And how did you find Oregon? Let me fix you tea. Have you had breakfast?”

“No time. And remarkable. Lush and verdant. The kind of place to lure a man’s soul and keep him bound forever. No to breakfast. I’ve much to do.”

“So we’ll be heading west then?”

For an instant his bright eyes flickered and he looked beyond her before he said, “Yes. I expect so.” He kissed her on her hair doily then, patted her back, and said he’d help her harness the buggy so she could join him at Lavina’s. “I’m anxious to spend time with my wife and children. Gather with us today.”

“I can do the harnessing myself. No tea?”

“Had some already. Just wanted the invite to come from me.”

“An invite?”

He nodded, put his floppy hat back on. “At our place. I’ve stories to tell.”

“I imagine you do. Off with you, then. I’ll tend Beatrice and harness my Joey.”

“That chicken hasn’t found the stew pot yet?”

“Hush! She’ll hear you.” She pushed at him. “Take Lavina in your arms and thank her for the amazing job she’s done while you gallivanted around new country. I’ll say a prayer of thanksgiving that you’re back safely.”

“See you in a few hours then.”

“Oh, I’ll arrive before that. What do you take me for, an old woman?” Beatrice clucked. “Keep your opinions to yourself.”

Orus laughed, picked his mother up in a bear hug, and set her down. “It’s good to see you, Marm. I thought of you often.” He held her eyes, started to speak. Instead he sped out the door, mounting his horse in one fluid movement, reminding her of his small-boy behavior of rarely sitting still, always in motion. Wonder where his pack string is? She scooped up Beatrice, buried her nose in her neck feathers, inhaling the scent that always brought comfort.

But what was that wariness she’d witnessed in her son’s eyes when she suggested that they’d all head west? She guessed she’d find out soon enough.

Jane Kirkpatrick, This Road We Traveled Revell Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2016.

Jane Kirkpatrick takes us on a perilous factor of choices made by real people and their outcomes by stories passed on through faith and diligence. Part of the story I am saying, "No, don't go that way!" Have you been cautioned and chose your own way? We learn from the past, to go forward.

I always learn so much from her stories. Perseverance, triumphs and failures, the drive to go ahead, mending of ways, a truth revealed. A time past applicable to today. For there is nothing new under the sun. Overcoming obstacles, encouraging others, an unexplored land, a dream. It is interesting that in the research other figures from previous stories written have met each other ~ crossing paths happened upon unsuspectingly until sought out.

Author Jane Kirkpatrick and her husband, Jerry, live in Central Oregon. Learn more at her website.

***Thank you to Revell Reads for inviting me to be part of the book tour for Jane Kirkpatrick's This Road We Traveled and for sending a review copy to me. This review was written in my own words. No other compensation was received.***

No comments:

Post a Comment