The rain didn’t amount to much—it was hardly worth the wait. Armina kicked off her shoes, careful to not disturb the kerosene-daubed rags she’d tied around her ankles to discourage chiggers.That's all I need? The chiggers keep me housebound. They wait at the edge of the lawn ~wait, wait, here she comes.

--Tattler's Branch, 1

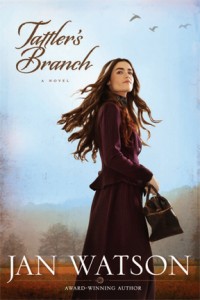

Dr. Lilly Corbett Still is the medical doctor in Skip Rock, a small mining community in the Kentucky mountains. Her friend Armina's husband, Ned, is continuing his education in Boston to come back full-fledged as a registered nurse in Dr. Still's practice. Her younger sister, Mazy, has come to spend the summer at Skip Rock, as Lilly's husband, Tern, is away on mining business. These three women are changed by summer's end by responsibilities and concerns they never saw coming. As they are strengthened and a support in the community, nearby Tattler's Branch brings unexpected trials and blessings.

I liked how the villain in the story turns out to be responsible in the end. I would like to read a further story of the happenings in the lives of these families. I have enjoyed all of Jan Watson's novels and continue to look forward to her work. The people are genuine and likable. I was hoping there would be a berry recipe for the cobbler! Each morning opens with you ready to meet the day with them. Jan's writing style is not only a telling but bringing you right in with them.

Enjoy the first chapter of Tattler's Branch by Jan Watson

Chapter 1

1911

Armina Tippen’s muscles twitched like frog legs in a hot skillet. She leaned against the deeply furrowed trunk of a tulip poplar to wait out an unexpected change in the weather and to gather her strength. The spreading branches of the tree made the perfect umbrella. Gray clouds tumbled across the sky as quarter-size raindrops churned up the thick red dust of the road she’d just left.

The rain didn’t amount to much—it was hardly worth the wait. Armina kicked off her shoes, careful to not disturb the kerosene-daubed rags she’d tied around her ankles to discourage chiggers. She didn’t have to fool with stockings because she wasn’t wearing any.

Back on the road, she ran her toes through the damp dirt. It was silky and cool against her skin. The only thing better would have been a barefoot splash in a mud puddle. There should be a law against wearing shoes between the last frost of spring and the first one of fall. Folks were getting soft, wearing shoes year-round. Whoever would have thought she’d be one of them? Knotting the leather strings, she hung the shoes around her neck and walked on.

Clouds blown away, the full force of the summer sun bore down, soothing her. She poked around with the walking stick she carried in case she got the wobbles and to warn blacksnakes and blue racers from the path. Snakes did love to sun their cold-blooded selves.

She hadn’t been up Tattler’s Branch Road for the longest time. For some reason she’d woken up thinking of the berries she used to pick here when she was a girl and living with her aunt Orie. Probably somebody else had already stripped the blackberry bushes of their fruit, but it didn’t hurt to look. There weren’t any blackberries like the ones that grew up here.

After she crossed the narrow footbridge that spanned this branch of the creek, she spied one bramble and then another mingling together thick as a hedge. Her mouth watered at the sight. Mayhaps she should have brought a larger tin than the gallon-size can hanging from her wrist. Or maybe two buckets . . . but then she couldn’t have managed her walking stick. Life was just one puzzle piece after another.

Armina stopped to put her shoes back on. It wouldn’t do to step on something unawares, although the sting from a honeybee sometimes eased her aches and pains. You’d think she was an old lady. She couldn’t remember the last time she felt like her twenty-year-old self. But if she stopped to figure on it, it seemed like her health had started going south in the early spring while she was up at the family farm helping her sister plant a garden. She’d caught the quinsy from one of the kids, more than likely her nephew Bubby. He was the lovingest child, always kissing on her and exchanging slobbers. When her throat swelled up inside, her sister had put her to bed with a poultice made up of oats boiled in vinegar and stuffed in a sock that draped across her neck to sweat out the poison. It was two days before she could swallow again.

The rusty call of pharaoh bugs waxed and waned as she pushed through the tall weeds and grasses growing along the bank. She’d loved playing with the locusts’ cast-off hulls when she was little. She would stick them on the front of her dress like play-pretty jewels. Not that she liked adornments—she mostly agreed with St. Paul on that particular argument. But she did like something pretty to fasten the braid of her hair into a bun at the nape of her neck. At the moment, her hairpin was a brilliant blue-jay’s feather.

The blackberry vines tumbled willy-nilly over a wire fence. She disremembered the fence; it seemed like there’d been easy access to the fruit. To her right was a gate free of creepers, but she wouldn’t trespass. There was more than enough fruit this side of the hindrance for the cobbler she aimed to make for supper. Doc Lilly loved her blackberry cobbler, especially with a splash of nutmeg cream. Ned did too, but he wasn’t at home. Just like Doc Lilly’s husband, Ned was off doing whatever it was men had to do to make their precarious way in this old world. Armina missed her husband and his sweet ways.

She walked down the line of bushes to the most promising ones and let her stick rest against the branches. With one hand she lifted a briar and with the other she plucked the fruit, filling the bucket in less than five minutes. The berries were big as double thumbs and bursting with juice, so heavy they nearly picked themselves. She didn’t have to twist the stems at all. In another day they’d be overripe, fermenting; then the blackbirds would finish them off, flying drunkenly from one heavily laden bush to another.

Her mind was already on the crust she’d make with a little lard and flour and just a pinch of salt. Maybe she’d make a lattice crust, although a good blackberry cobbler didn’t need prettying up.

Armina slid the container off her wrist and bent to set it down. When she raised her head, specks like tiny black gnats darted in and out of her vision. Lights flashed and she lost her balance, falling backward through the prickly scrub. She landed against the fence with her legs stuck straight out like a lock-kneed china doll.

“For pity’s sake,” she said with a little tee-hee. “I hope I didn’t kick the bucket.” A scratch down her cheek stung like fire, and one sleeve of the long-tailed shirt she wore open over her dress was torn, but otherwise she reckoned she was all of a piece. There was nothing to do but wait a few minutes for her head to stop swimming. Then, if she could get her knees to work, she could crawl out.

It was cool here behind the bushes—and peaceful. A few feet away, a rabbit hopped silently along. A miniature version of itself followed closely behind. Their twitching whiskers were stained purple. Brer Rabbit and his son, Armina fancied as she watched their cotton-ball tails bob.

Suddenly the gate slammed against the bushes. Blackberry fronds waved frantically as if warning her of a coming storm. Startled, Armina parted the brambles and peered out. A couple wrestled silently toward the creek. A man with long yellow hair slicked back in a tail had a woman clamped around the neck with his forearm. He pulled her along like a gunnysack full of potatoes. The woman bucked and struggled to no avail as they splashed into the water this side of the footbridge.

The woman broke free, gasping for air. She was going to make it, Armina saw; she was going to escape. But instead of running away while she had the chance, the woman charged back toward the man, swinging on him. The man’s hand shot out and seized a hank of her disheveled hair. He reeled her in like a fish on the line and they both went under. When they came up, the man held a large round rock that glinted wetly in the sun.

Armina opened her mouth, but the rock smashing down and the water arcing up in a spray of red stilled her voice, which had no more power than the raspy call of the molting locusts.

The man bent over with one hand holding the rock and the other resting on his thigh. His chest heaved in and out like a bellows. The rabbit zigzagged out of the bushes, leaving the little one cowering behind. The man straightened, looking all around out of stunned eyes.

The world had gone still as a churchyard greeting a funeral procession. Armina didn’t dare to breathe. If he saw her feet sticking out from under the bushes, she was dead. She felt sick to her stomach, and her brain spun like a top. She willed the spinning to stop, but it paid her no mind as everything faded to black.

When Armina awoke, it was like nothing untoward had happened. Birds chirped and water burbled in the creek. The little rabbit’s whiskers twitched nervously as it munched on white clover.

Armina was ravenously hungry and bone-dry thirsty. She could never get enough to drink anymore. She picked a handful of the berries and ate them. If she wanted water, she’d have to get it from the creek. No way could she do that after what had happened. She’d been more than foolish not to bring a fruit jar full.

She felt like she’d wakened from a nightmare. Lately she’d been having strange dark spells and bright-colored auras. Doc Lilly would be mad that she hadn’t told her, but Armina didn’t much like sharing. Besides, if she told, Doc would list a bunch of preventatives that Armina wouldn’t pay any mind to. She liked being in charge of her own self.

Pulling her knees up to her chest, she tested the strength in her legs—looked like she was good to go. She crawled out from under the brambles.

She wasn’t one bit wobbly as she marched to the footbridge and went straight across, looking neither to the right nor to the left. The bridge felt good and solid under her feet, just like it should. The sun shone brightly, as it would on any normal July day. Her legs were sturdy tools carrying her along toward home just like legs were made to do. It was fine. Every little thing was fine—except she was missing her red berry bucket and her strong white sycamore walking stick. She’d have to go back.

A trill of fear crept up her spine. From under the bridge, the rushing water called for her to look—look there, just on the other side. Look where the smooth round rock waited in judgment. She swallowed hard and heeded the water’s call.

Armina felt faint with relief. There was no body in the branch. Her mind had played a trick on her just as she thought.

It was going to be a trick of another sort to find her stick, which had surely fallen among the brambles. She nearly laughed aloud. It was so good to have such a simple problem.

If she hadn’t stopped at the water’s edge—if she’d gone on home—she would never have seen the trail of dark-red splotches. If she’d gone on home, she would not have followed them up and beyond the garden gate. It was blood; she knew it was. It smelled metallic, like your palm smelled if you ran it over the frame of an iron bedstead. She wished she’d never stopped. Now she was compelled to follow that ominous trail.

Armina heard the baby’s cry before she saw the cabin. It was a mewling, pitiful cry, nothing like the lusty bawls her niece and nephew had made when they were newborns, but still she knew that sound.

The house sat nestled in a grove of trees, as cozy as a bird’s nest in thick cedar branches. The place was neat, the yard free of weeds and the porch swept clean. Merry flowers blossomed in a small garden beside the porch steps. Armina could make out zinnias and marigolds from where she lurked behind a tree. A zinc watering can lay overturned on the top step. In the side yard, a wire clothesline sagged beneath the weight of a dozen sun-bleached diapers. She didn’t see a body but there had to be one somewhere close. That woman from the creek just didn’t up and walk away—not after losing all that blood.

The man with the yellow hair came out the open door and hurried down the steps. He picked up some tools that leaned against the porch railing—a shovel and a pickax— then paused for a moment in the yard and rubbed his chin, keeping his back to the door. The baby’s cry persisted. He turned like he might go back inside, but he didn’t.

Armina hunched her shoulders and pressed up against the tree, praying he wouldn’t come her way. After a while, she could hear the distant sound of the pick or the shovel grating against rock. When she peeled herself away from the tree, she could feel the print of black walnut bark on her cheeks.

As quick as Brer Rabbit, she ran to the near side of the cabin and stooped down under an open window until she dared to look inside. Just under the window sat a Moses basket holding an infant with dandelion-yellow hair and a strange foreign face. A nearly full baby bottle rested on a rolled towel, the rubber nipple just shy of the baby’s mouth.

What sort of mother would try to feed a baby this young from a prop? No wonder it cried so piteously.

Armina listened for the sound of digging. If the man was grubbing a grave out of this unforgiving earth, it would take a while. She figured she was safe as long as she could hear the scrape of metal against stone.

“Legs, don’t fail me now,” she pleaded under her breath. Taking hold of the window ledge with both hands, she clambered over the sill. She didn’t hesitate, just grabbed the handles of the woven basket and with one swoop set it in the thin grass outside the window. She climbed out and went to the clothesline in the side yard. With quick jerks that popped the clothespins off, she helped herself to the dozen diapers. If she was going to steal a baby, she might just as well steal its diapers.

Clutching the basket to her chest, she ran back the way she had come. Even over the sound of her feet pounding across the bridge, she fancied she could hear the swing of a pickax rending the air, bearing down on rock.

1911

Armina Tippen’s muscles twitched like frog legs in a hot skillet. She leaned against the deeply furrowed trunk of a tulip poplar to wait out an unexpected change in the weather and to gather her strength. The spreading branches of the tree made the perfect umbrella. Gray clouds tumbled across the sky as quarter-size raindrops churned up the thick red dust of the road she’d just left.

The rain didn’t amount to much—it was hardly worth the wait. Armina kicked off her shoes, careful to not disturb the kerosene-daubed rags she’d tied around her ankles to discourage chiggers. She didn’t have to fool with stockings because she wasn’t wearing any.

Back on the road, she ran her toes through the damp dirt. It was silky and cool against her skin. The only thing better would have been a barefoot splash in a mud puddle. There should be a law against wearing shoes between the last frost of spring and the first one of fall. Folks were getting soft, wearing shoes year-round. Whoever would have thought she’d be one of them? Knotting the leather strings, she hung the shoes around her neck and walked on.

Clouds blown away, the full force of the summer sun bore down, soothing her. She poked around with the walking stick she carried in case she got the wobbles and to warn blacksnakes and blue racers from the path. Snakes did love to sun their cold-blooded selves.

She hadn’t been up Tattler’s Branch Road for the longest time. For some reason she’d woken up thinking of the berries she used to pick here when she was a girl and living with her aunt Orie. Probably somebody else had already stripped the blackberry bushes of their fruit, but it didn’t hurt to look. There weren’t any blackberries like the ones that grew up here.

After she crossed the narrow footbridge that spanned this branch of the creek, she spied one bramble and then another mingling together thick as a hedge. Her mouth watered at the sight. Mayhaps she should have brought a larger tin than the gallon-size can hanging from her wrist. Or maybe two buckets . . . but then she couldn’t have managed her walking stick. Life was just one puzzle piece after another.

Armina stopped to put her shoes back on. It wouldn’t do to step on something unawares, although the sting from a honeybee sometimes eased her aches and pains. You’d think she was an old lady. She couldn’t remember the last time she felt like her twenty-year-old self. But if she stopped to figure on it, it seemed like her health had started going south in the early spring while she was up at the family farm helping her sister plant a garden. She’d caught the quinsy from one of the kids, more than likely her nephew Bubby. He was the lovingest child, always kissing on her and exchanging slobbers. When her throat swelled up inside, her sister had put her to bed with a poultice made up of oats boiled in vinegar and stuffed in a sock that draped across her neck to sweat out the poison. It was two days before she could swallow again.

The rusty call of pharaoh bugs waxed and waned as she pushed through the tall weeds and grasses growing along the bank. She’d loved playing with the locusts’ cast-off hulls when she was little. She would stick them on the front of her dress like play-pretty jewels. Not that she liked adornments—she mostly agreed with St. Paul on that particular argument. But she did like something pretty to fasten the braid of her hair into a bun at the nape of her neck. At the moment, her hairpin was a brilliant blue-jay’s feather.

The blackberry vines tumbled willy-nilly over a wire fence. She disremembered the fence; it seemed like there’d been easy access to the fruit. To her right was a gate free of creepers, but she wouldn’t trespass. There was more than enough fruit this side of the hindrance for the cobbler she aimed to make for supper. Doc Lilly loved her blackberry cobbler, especially with a splash of nutmeg cream. Ned did too, but he wasn’t at home. Just like Doc Lilly’s husband, Ned was off doing whatever it was men had to do to make their precarious way in this old world. Armina missed her husband and his sweet ways.

She walked down the line of bushes to the most promising ones and let her stick rest against the branches. With one hand she lifted a briar and with the other she plucked the fruit, filling the bucket in less than five minutes. The berries were big as double thumbs and bursting with juice, so heavy they nearly picked themselves. She didn’t have to twist the stems at all. In another day they’d be overripe, fermenting; then the blackbirds would finish them off, flying drunkenly from one heavily laden bush to another.

Her mind was already on the crust she’d make with a little lard and flour and just a pinch of salt. Maybe she’d make a lattice crust, although a good blackberry cobbler didn’t need prettying up.

Armina slid the container off her wrist and bent to set it down. When she raised her head, specks like tiny black gnats darted in and out of her vision. Lights flashed and she lost her balance, falling backward through the prickly scrub. She landed against the fence with her legs stuck straight out like a lock-kneed china doll.

“For pity’s sake,” she said with a little tee-hee. “I hope I didn’t kick the bucket.” A scratch down her cheek stung like fire, and one sleeve of the long-tailed shirt she wore open over her dress was torn, but otherwise she reckoned she was all of a piece. There was nothing to do but wait a few minutes for her head to stop swimming. Then, if she could get her knees to work, she could crawl out.

It was cool here behind the bushes—and peaceful. A few feet away, a rabbit hopped silently along. A miniature version of itself followed closely behind. Their twitching whiskers were stained purple. Brer Rabbit and his son, Armina fancied as she watched their cotton-ball tails bob.

Suddenly the gate slammed against the bushes. Blackberry fronds waved frantically as if warning her of a coming storm. Startled, Armina parted the brambles and peered out. A couple wrestled silently toward the creek. A man with long yellow hair slicked back in a tail had a woman clamped around the neck with his forearm. He pulled her along like a gunnysack full of potatoes. The woman bucked and struggled to no avail as they splashed into the water this side of the footbridge.

The woman broke free, gasping for air. She was going to make it, Armina saw; she was going to escape. But instead of running away while she had the chance, the woman charged back toward the man, swinging on him. The man’s hand shot out and seized a hank of her disheveled hair. He reeled her in like a fish on the line and they both went under. When they came up, the man held a large round rock that glinted wetly in the sun.

Armina opened her mouth, but the rock smashing down and the water arcing up in a spray of red stilled her voice, which had no more power than the raspy call of the molting locusts.

The man bent over with one hand holding the rock and the other resting on his thigh. His chest heaved in and out like a bellows. The rabbit zigzagged out of the bushes, leaving the little one cowering behind. The man straightened, looking all around out of stunned eyes.

The world had gone still as a churchyard greeting a funeral procession. Armina didn’t dare to breathe. If he saw her feet sticking out from under the bushes, she was dead. She felt sick to her stomach, and her brain spun like a top. She willed the spinning to stop, but it paid her no mind as everything faded to black.

When Armina awoke, it was like nothing untoward had happened. Birds chirped and water burbled in the creek. The little rabbit’s whiskers twitched nervously as it munched on white clover.

Armina was ravenously hungry and bone-dry thirsty. She could never get enough to drink anymore. She picked a handful of the berries and ate them. If she wanted water, she’d have to get it from the creek. No way could she do that after what had happened. She’d been more than foolish not to bring a fruit jar full.

She felt like she’d wakened from a nightmare. Lately she’d been having strange dark spells and bright-colored auras. Doc Lilly would be mad that she hadn’t told her, but Armina didn’t much like sharing. Besides, if she told, Doc would list a bunch of preventatives that Armina wouldn’t pay any mind to. She liked being in charge of her own self.

Pulling her knees up to her chest, she tested the strength in her legs—looked like she was good to go. She crawled out from under the brambles.

She wasn’t one bit wobbly as she marched to the footbridge and went straight across, looking neither to the right nor to the left. The bridge felt good and solid under her feet, just like it should. The sun shone brightly, as it would on any normal July day. Her legs were sturdy tools carrying her along toward home just like legs were made to do. It was fine. Every little thing was fine—except she was missing her red berry bucket and her strong white sycamore walking stick. She’d have to go back.

A trill of fear crept up her spine. From under the bridge, the rushing water called for her to look—look there, just on the other side. Look where the smooth round rock waited in judgment. She swallowed hard and heeded the water’s call.

Armina felt faint with relief. There was no body in the branch. Her mind had played a trick on her just as she thought.

It was going to be a trick of another sort to find her stick, which had surely fallen among the brambles. She nearly laughed aloud. It was so good to have such a simple problem.

If she hadn’t stopped at the water’s edge—if she’d gone on home—she would never have seen the trail of dark-red splotches. If she’d gone on home, she would not have followed them up and beyond the garden gate. It was blood; she knew it was. It smelled metallic, like your palm smelled if you ran it over the frame of an iron bedstead. She wished she’d never stopped. Now she was compelled to follow that ominous trail.

Armina heard the baby’s cry before she saw the cabin. It was a mewling, pitiful cry, nothing like the lusty bawls her niece and nephew had made when they were newborns, but still she knew that sound.

The house sat nestled in a grove of trees, as cozy as a bird’s nest in thick cedar branches. The place was neat, the yard free of weeds and the porch swept clean. Merry flowers blossomed in a small garden beside the porch steps. Armina could make out zinnias and marigolds from where she lurked behind a tree. A zinc watering can lay overturned on the top step. In the side yard, a wire clothesline sagged beneath the weight of a dozen sun-bleached diapers. She didn’t see a body but there had to be one somewhere close. That woman from the creek just didn’t up and walk away—not after losing all that blood.

The man with the yellow hair came out the open door and hurried down the steps. He picked up some tools that leaned against the porch railing—a shovel and a pickax— then paused for a moment in the yard and rubbed his chin, keeping his back to the door. The baby’s cry persisted. He turned like he might go back inside, but he didn’t.

Armina hunched her shoulders and pressed up against the tree, praying he wouldn’t come her way. After a while, she could hear the distant sound of the pick or the shovel grating against rock. When she peeled herself away from the tree, she could feel the print of black walnut bark on her cheeks.

As quick as Brer Rabbit, she ran to the near side of the cabin and stooped down under an open window until she dared to look inside. Just under the window sat a Moses basket holding an infant with dandelion-yellow hair and a strange foreign face. A nearly full baby bottle rested on a rolled towel, the rubber nipple just shy of the baby’s mouth.

What sort of mother would try to feed a baby this young from a prop? No wonder it cried so piteously.

Armina listened for the sound of digging. If the man was grubbing a grave out of this unforgiving earth, it would take a while. She figured she was safe as long as she could hear the scrape of metal against stone.

“Legs, don’t fail me now,” she pleaded under her breath. Taking hold of the window ledge with both hands, she clambered over the sill. She didn’t hesitate, just grabbed the handles of the woven basket and with one swoop set it in the thin grass outside the window. She climbed out and went to the clothesline in the side yard. With quick jerks that popped the clothespins off, she helped herself to the dozen diapers. If she was going to steal a baby, she might just as well steal its diapers.

Clutching the basket to her chest, she ran back the way she had come. Even over the sound of her feet pounding across the bridge, she fancied she could hear the swing of a pickax rending the air, bearing down on rock.

No comments:

Post a Comment